Picking up The Girl Who Fell From the Sky last week – I had one of those ‘library love’ moments. Another reminder of the wonderfulness of libraries – I had been looking out for this novel since it was published in May and there it was – in a similar place to where I found Julia last week. For anybody in London who has access to an Ideas Store library – I can recommend taking a look.

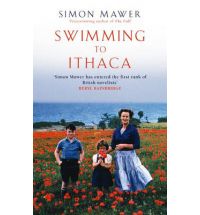

This is the third of Mawer’s books I’ve read since discovering him this year; The Glass Room (loved it), Swimming to Ithaca (liked it quite a bit) and now The Girl Who Fell From the Sky which I loved. That is a simple summary but it is actually easy to do as the stories are all quite different. The are all set against a background of war or conflict but the style of each is unique – and all enjoyable to read.

The Girl Who Fell From The Sky is Marian, also known as Alice or Anne-Marie or Laurent. British and a fluent French speaker, this is the story of her recruitment,training and eventual mission in France as a Special Operations Executive during World War II. It is such a fun story to read with a straightforward narrative style. Marian is a likeable, gutsy character and by keeping control of the scope of the story, the author creates time to spend on the little details making Marian seem all the more authentic. I won’t write too much about her mission, Operation Trapeze, except to say it has all the danger and multi layered intrigue you might expect. This is a mission of such importance that nothing is off limits, including family bonds and personal relationships.

This is the simplest telling of the books I have read so far by Simon Mawer. The Glass Room was arty and haunting and there was a dual narrative in Swimming to Ithaca. Apart from the title which I didn’t especially like (fairly or not, it reminded me of Stieg Larsson’s Millenium series), The Girl Who Fell From The Sky was my favourite of the books to read – if things like sleep and work hadn’t got in the way, I would have read it in one sitting.